Article - The Best Example To Explain Optimism Bias Phenomenon

Submitted by Jamal Moustafaev on Tue, 09/15/2015 - 16:25

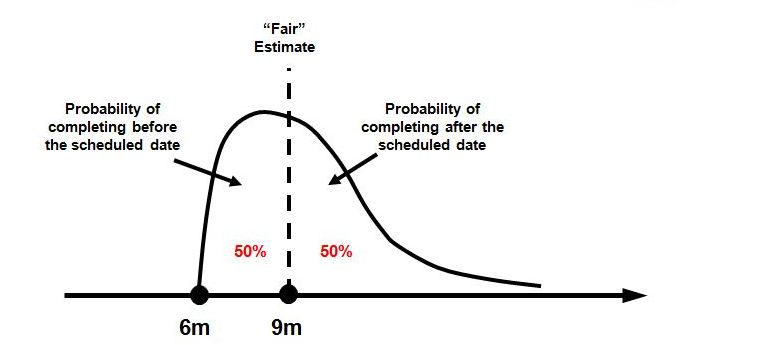

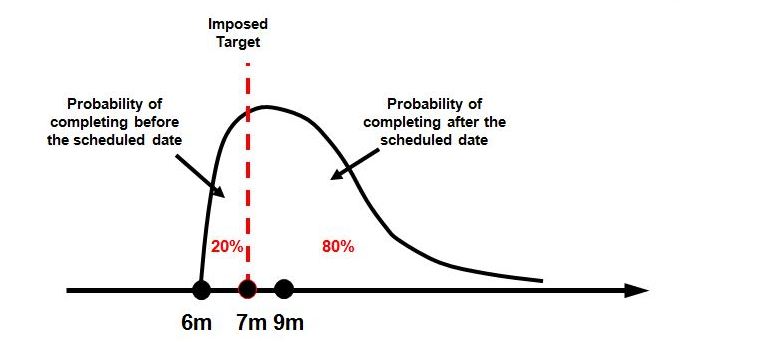

As a part of my project management course I frequently have to talk about the estimation-related phenomenon known as "optimism bias". Succinctly stated optimism bias is described as follows:

We as the species of homo sapiens tend to overestimate our abilities required to perform a specific task and underestimate the complexity of the task in question

Usually when one provides his audience with a complicated and slightly boring definition, he has to follow up with a clear, simple and hopefully entertaining example. Throughout my consulting and teaching career I tried using a number of case studies including pretty much every megaproject on this list. However each and every example used has been met with mixed feelings. Sometimes people never heard about the Denver Airport Baggage Handling system and sometimes they failed to see the connection between optimism bias and the overall project failure.

I kinda gave up on finding the best illustration for this phenomenon, until one of my friends told me the following story:

His son has just started going to the kindergarten and he and his wife agreed that he would pick them up from the bus station located not too far from their home. They have also agreed that his wife would give him a call once she was ready to leave the office (kindergarten was located nearby). So at one point of time he receives a call from his significant other stating that he should pick them up at the bus stop in 15 minutes. Being a responsible person he exits his home right away and arrives at the bus station with 5 minutes to spare.

Five, ten, fifteen, thirty minutes go by. No sign of his wife and kid. Finally forty minutes after the expected deadline (sorry for the project management nerd talk) his family exits from the bus ... The following conversation ensues:

H: Where have you been? I have been waiting here for more than half an hour! And more importantly, why did you tell me it would take you 15 minutes to get here?